Buried in Paper:

The D-Day Documents

Fascinating and Poignant Stories Revealed in Actual World War II Documents

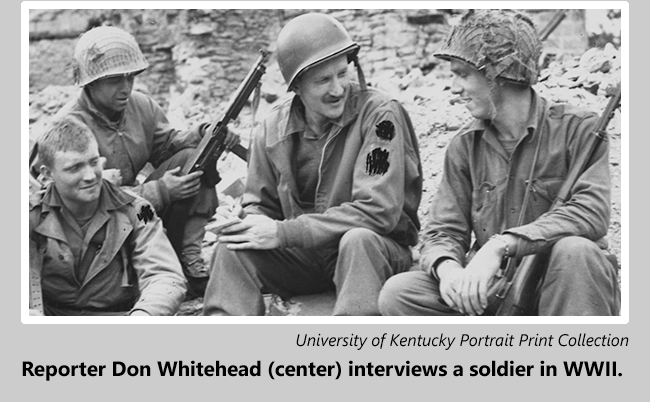

Associated Press reporter Don Whitehead wrote this account of landing on Omaha Beach with the 16th Infantry Regiment on D-Day for the Society of the First Division in 1948. It's one of a collection of first-person accounts by war correspondents assigned to the division. The collection can be found here in the archives of the First Division Museum in Wheaton, Illinois.

Associated Press reporter Don Whitehead wrote this account of landing on Omaha Beach with the 16th Infantry Regiment on D-Day for the Society of the First Division in 1948. It's one of a collection of first-person accounts by war correspondents assigned to the division. The collection can be found here in the archives of the First Division Museum in Wheaton, Illinois.

Whitehead was in the thick of it: The 16th Infantry was awarded a Distinguished Unit Citation for its actions on D-Day. This citation is given to units that "display such gallantry, determination, and esprit de corps in accomplishing its mission under extremely difficult and hazardous conditions as to set it apart from and above other units in the same campaign." To read the actual citation, click here

Whitehead was 36 when he landed with on Omaha Beach. He also reported on the liberation of Paris, the meeting of Russian and American troops at the Elbe River and the liberation of Buchenwald. He later won two Pulitzer prizes covering the Korean War.

Normandy: As I Saw It

By Don Whitehead

The first soft layer of dusk had fallen over drab, war-weary London and veiled the patched windows of my Chelsea flat when the telephone rang. It was Ernie Pyle calling.

"Hey, Don," he said. "Come on over. I'm lonesome and want to share my jitters."

I left the flat and took one of London's funny little cabs through Hyde Park to the Dorchester Hotel where I found Ernie in his room finishing a column. He waved to a bottle on the table.

"Real Kentucky bourbon," he grinned. "I never saw the guy before in my life, but he wanted to give me the bottle and I wouldn't argue."

I helped Ernie re-type his column and then we sat and talked of invasion and the chances for success.

Nervous tension was mounting all over England and Ernie wasn't the only one troubled by the jitters. We all knew the invasion of Hitler's European fortress was drawing near but few of us knew the closely guarded secret of when. Nor did I want to know. The responsibility of knowing would have been too great.

The correspondents had been alerted to move out of London quickly, those of us going in with the assault troops. Our field equipment was packed. Now there was nothing to do but wait for the final call. The date was May 28, 1944.

Even then the little guy had a premonition that he would not live through the war. In unguarded moments his face was sad. He didn't like to be alone and he drew his friends around him as though they were a shield against some dark fear that was closing in on him.

I drew the blackout curtains and switched on the light.

"Who are you going with?" Ernie asked.

"I don't know," I said. "I hope it's the First Division. In my books the 1st is the greatest infantry division we've got."

Ernie nodded. "You can't go wrong with the 1st. I guess the 1st still is my favorite but I'm assigned to Bradley's headquarters. We'll be in about D plus 1."

Later we joined a group of correspondents at the Savoy and made a round of London night spots. Behind the blackout curtains there was music, laughter, glitter and a sort of reckless gaiety to ease the tension and the loneliness. Dawn was near when the party broke up.

It seemed I hardly had closed my eyes when the phone rang. I was ordered to report, with field equipment, to an address near Hyde Park. And when I arrived I found Ernie and friends from other campaigns lugging their gear into the office of Lieutenant Colonel Jack Redding, public relations officer. We sensed this call was the real thing and not another cover-up maneuver.

National Archives

Ernie Pyle's D-Day experience

Because of a last-minute change, Ernie Pyle, probably the most famous WWII war correspondent, didn't get to Omaha Beach until D-Day+1. Here's some of what he saw (excerpted from a column titled "A Pure Miracle" reprinted by Indiana University. Pyle was killed less than a year later during the Battle of Okinawa.

"... Submerged tanks and overturned boats and burned trucks and shell-shattered jeeps and sad little personal belongings were strewn all over these bitter sands. That plus the bodies of soldiers lying in rows covered with blankets, the toes of their shoes sticking up in a line as though on drill. And other bodies, uncollected, still sprawling grotesquely in the sand or half hidden by the high grass beyond the beach.

"That plus an intense, grim determination of work-weary men to get this chaotic beach organized and get all the vital supplies and the reinforcements moving more rapidly over it from the stacked-up ships standing in droves out to sea. …"

After lunch we were driven from London in jeeps which headed toward the southeast, traveling back roads where there was little traffic. We spent the night in a dreary temporary camp and next morning our little group separated to fan out to the various assault units in their assembly points.

Jack Thompson of the Chicago Tribune—an old friend from the North African, Sicily and Italy campaigns—and I were driven to an old English country house outside Portland. My heart leaped as I recognized our destination—Danger Forward, the headquarters of the 1st Infantry Division!

Major Owen B. Murphy of Lexington, Kentucky, said: "I've been throwing another extra sock in my bag each time I heard a rumor we were leaving. Now that you boys have shown up, I guess it's official."

It was good to see Colonel Stan Mason, the Division's chief of staff who had helped direct the 1st from the beaches of North Africa through Tunisia arid Sicily. Stan Mason was one of the big reasons why the First Division was a great division.

And there was lanky Lieutenant Colonel Robert Evans, the cap ble G-2, and Major Paul Gale, big Lieutenant Maxie Zera from the Bronx with a heart as big as his voice, and many others who had made the long trip with the 1st.

We walked into the headquarters and Bob Evans introduced us to Major General Clarence R. Huebner—one of the finest soldiers and gentlemen I've ever known.

The general welcomed us warmly and with a sly humor.

"We're glad to have you with us," he said. "We'll do everything we can to help you get your stories. The people at home must know what we are doing. If you are wounded, we will put you in a hospital. If you are killed, we will bury you. So don't worry!"

I looked closely at this man whose division had been given the tremendous responsibility of leading the invasion assault, saw a kindly face with a square jaw and direct blue eyes that twinkled with humor. I judged he was in his early fifties. He was physically fit and there was an air of confidence about him that I liked.

I found that Huebner had a great love for his 1st Division. He enlisted as a young man in the 18th Regiment and had come up the hard way through the ranks, distinguishing himself in the First World War. He knew the job of every man in his division as well or better than the men knew the jobs—because he had once held those jobs himself.

The general wanted his division to be the best in the entire Army. It wasn't entirely a matter of personal pride because Huebner knew that the toughest, straightest-shooting division won its objectives with the least loss of life. And if he was stern in his discipline, it was because battle casualties have a direct relation to discipline.

We made ourselves at home with the 1st, waiting for the call to go aboard ship. In the marshalling area, the equipment was being loaded and the troops were boarding the transports, LST's, LCI's and other invasion craft which jammed the harbor. Everywhere there was great activity.

Three of the busiest men in the marshalling area were Colonel George Taylor, commanding the 16th Regimental Combat Team; tall, quiet-spoken Brigadier General Willard G. Wyman, assistant divisional commander, and leathery Brigadier General Clift Andrus, division artillery officer (who later was to become the commanding general of the Fighting 1st).

I knew Taylor and Andrus well and seeing them reminded me of the Sicily invasion. Taylor's regiment had run into trouble when the Germans attacked the one-day-old beachhead with tanks. The 16th had fought tanks literally with everything but their bare fists and when it looked as though the tanks would smash the beach head—Andrus' artillery turned the tide.

Clift Andrus was recognized as one of the finest artillerymen in World War II. And there on the beaches of Sicily he proved it. With only a few guns ashore, he got them into action almost at the water's edge and broke the counterattack. He had his artillerymen blasting at the tanks at close range over open sights in what was undoubtedly one of the great artillery battles of the war.

It was little wonder, traveling with men like these, that I felt secure when we went aboard the Coast Guard transport, Samuel Chase, on June 4. The Chase was the headquarters ship for Taylor's 16th Regimental Combat Team.

For 24 hours a storm swept the channel and kept the great invasion armada at anchor. But next day General Eisenhower made his decision and the fleet steamed under cover of darkness toward the beaches of Normandy.

There was a strange lack of excitement among the men aboard the Chase. In fact they seemed relieved the long wait was over, and that within the next few hours or days a decision would be reached in battle. Reality is so much easier to face than the subtle fear of the unknown and the waiting … waiting … waiting …

In the ship's hold, company commanders, platoon and section leaders studied a giant sponge rubber map of the Normandy coast Every house, out-building, ridge, tree and hedgerow was faithfully reproduced on the model designed from photographs of the beaches where the 16th was to land. The men were memorizing every detail of the landscape which would help them in battle, figuring how best to reach their objectives while giving their men as much protection as possible from enemy fire.

They knew all that photographs and military intelligence could tell them about the terrain and the enemy defenses. But what they could not know was that, while they studied their maps and models, the enemy was moving a full division of infantry into the positions they were to attack!

This was a cruel, blind stroke of luck, this sudden shifting of the 352nd Division to the beach where the 1st was to land in the center of the Allied invasion drive. It placed the burden squarely on the Fighting 1st and no other assault force was to meet such a test of courage and stamina on the beaches of Normandy.

Up in the wardroom of the Chase, there was little to remind one of the tremendous drama being enacted. A poker game was in progress. A few watched the shifting luck of the cards. Others wrote letters or read books. If anyone mentioned what was ahead, it was with a wisecrack to mask his feelings.

Luck was running against a young captain in the poker game.

"Jim," he said, "give me another fifty pounds."

Jim shoved a wad of bank notes across the table.

"I'll pay you back …"

"Forget it! It's nothing but money!"

Later that night, Jack Thompson and I went to the cabin of Colonel Taylor and he unfolded the plan of invasion for us. Not until we were underway did we know our destination and how the Allies planned to smash into Europe.

The 16th Regimental Combat Team—supported by the 116th Regiment of the 29th Infantry division—was spearheading the center of the invasion on the beach ^th the code name of "Omaha." The British was on our left and the American 4th Infantry Division was on our right.

Our initial assault force—known as "Force O"—numbered 34,000 men and 3,300 vehicles. This was the spearhead, a reinforced unit stronger than two ordinary divisions, packing a terrific wallop.

In addition to his own veteran 16th and 18th Regimental Combat Teams, Huebner was commanding the 116th Regimental Combat Team and the 115th Infantry, attached, from the 29th Division, a provisional Ranger force of two battalions, and attached units of artillery, armor, engineers and service units.

Following behind us was the 29th Division built up to a strength of 25,000 men and 4,400 vehicles. And the assault forces had to be clear of the beach in the afternoon or else the follow-up waves would pour in on them.

As the Colonel explained the plan, I stared at the contour lines of the maps and saw the section of the beach where our assault boat would land north of the little town of Colleville-sur-mer was called "Easy Red." I wondered how easy it would be and how red the sands before another sundown. I wondered how many thousands of those battle-tough, homesick youths bobbing around us in assault craft would get beyond the beach known as Easy Red.

I remembered the interview in London with General Omar Nelson Bradley a few days before we left to join the invasion troops. The tall, grave Missourian was sure Fortress Europe could be invaded without the terrifying loss of life predicted by the gloom mongers.

"The invasion will be in 3 phases," he said. "The first phase will be to get a toe hold on Europe. And that will be the most critical of all. Then will come the second phase, the build-up. We must pour men and guns and supplies ashore as rapidly as possible. The final phase will be to break out of our beachhead and destroy the enemy's armies. …

And I recalled sitting in a big drafty schoolroom in London and listening to Montgomery. He stood on a platform slim and straight with his hands behind his back, talking in his clipped, precise way like a headmaster lecturing a group of students.

"Rommel is a disrupter. Yes, he is a disrupter. He will commit himself on the beaches. He will try to knock us back into the sea. …"

Then Colonel Taylor's voice broke into my thoughts. "The first six hours will be the toughest," he said. "That is the period during which we will be the weakest. But we've got to open the door. Somebody has to lead the way—and if we fail … well … then the troops behind us will do the.job. They'll just keep throwing stuff onto the beaches until something breaks. That is the plan."

Suddenly and for the first time, I began to realize the magnitude of invasion and its relentless force. Tomorrow we would hit the beaches and behind us would come wave after endless wave of troops, guns, tanks, and supplies to beat against the coast of Normandy in a mounting tide. It was as though man for centuries had lived, begotten offspring and labored toward this moment which would shape the world's history for all time to come.

General Bradley had chosen the veterans of the Red One to lead the way. He knew they had been tempered for the task on the sands of Africa and in the gray dust of Sicily. He knew they would not fail him.

This was the greatest tribute the commanding general of the American First Army could have paid to a combat division—placing it in the spearhead of invasion. For if the First Division failed then the center of the invasion front might well collapse and drag down the entire invasion in bloody chaos. It had to succeed, no matter how bitter the cost!

The ship came to life before dawn. Bells rang, chains clanked, booted feet clumped on steel decks and the ship's loudspeakers blared orders.

This was the day!

I struggled into my stiff, impregnated clothes which were a shield against gas attack, checked my gear and went up on deck as dawn began to wash away the darkness in the east.

We heard the roar of bombers overhead and saw the flash of explosions where the bombs burst on shore. Our air force was giving the enemy gun positions a pasting before the troops hit the beach.

And then my stomach tightened. The voice over the loudspeaker called the number of our boat. Silently our little group climbed over the ship's rail in the darkness and into an assault boat. The gray side of the Chase loomed above us and the boat was pitching in the rough channel. A cold wind whipped salt spray against our cheeks like pellets of ice. The water soaked our clothing and ran into our boots in icy rivulets.

All around us the LCVP's churned through the waves with their cargoes of seasick, miserable troops, disgorged from the ships spread as far as one could see in the misty graw [sic] dawn of 6 June. Amphibious ducks and tanks wallowed through the waves like strange monsters of the deep.

The tanks were one of the "secret weapons" for invasion to give the assault troops added firepower. They were buoyed up by huge inflated canvas doughnuts which encircled them. They were to go in shooting. But the storm which had swept the channel had made it a death trap. The tank crews drove toward the beach but few reached shore. Most of the tanks were swamped in the 6-foot waves and carried their crews to the bottom of the channel before the men had a chance to fight.

We circled near the Chase for a few minutes and then headed for the beach. The senior officer in our boat was tall, lean Brigadier General Wyman who had been with Stilwell in Burma. Wyman was to go ashore as quickly as possible, direct operations at close range, and organize Danger Forward, the advance command post, so that General Huebner could transfer his headquarters from ship to shore. Until the command post was organized, the nerve center of the First Division would remain aboard a ship in the channel.

The pitching of the boat made me sick. My teeth chattered from cold and, I suspect, a liberal dash of fright. My stomach heaved with every lurch of the boat and I knew there were thousands like me. Major Paul Gale, who had been my companion on another landing in Sicily, grinned at me from under his helmet. I think Paul enjoyed the excitement and the sense, of impending danger, but his wisecracks designed to cheer me couldn't stop the heaving of my stomach.

Soon we could see the beach—Easy Red Beach—a hellish inferno of battle. Shells exploded in the surf and sent up small geysers while bullets whipped up ugly little spouts of water. The thunder of our naval gunfire and the explosion of shells rolled over us now. Above the crashing shells and the sharp slap of the waves against our boat was the murderous hissing of flying shells.

General Wyman ordered our boat to pull alongside a patrol craft from where he could get a radio report of the initial landings and learn how things were going. A few minutes later he returned to the boat.

The situation ashore was bad. Everything was confused and behind schedule. Casualties were heavy. The engineers had not been able to clear all the gaps planned through the beach defenses. The invasion was stalled and somebody had to get in and help bring order out of the confusion.

"We're going in," the General said.

We left the patrol craft and moved in with the assault waves. Our coxswain found a gap through the barriers of barbed wire, logs, steel spokes and mines. The smoke of battle boiled around us, and we crouched in the boat and peered over the side at the carnage and destruction. Somehow we raced through the gap in the barriers on the crest of a wave. The LCVP grounded and we ran down the ramp and waded through the surf to throw ourselves on the beach with thousands of others hugging that precious little strip of sand and gravel.

From the water's edge the beach shelved upward for about 30 feet. Beyond this was a flat, open stretch rising gradually to a bluff less than 300 yards away. The sloping gravel shelf gave some protection from the machinegun and rifle fire pouring from the German positions on the bluff. But there was no protection from the mortars and shells which screamed in from nowhere. The beach was a shooting gallery and the men who came out of the sea were the targets.

Many officers were killed before they could reach shore. They died as shells smashed into their boats or as they waded toward the beach or as they stood on the few feet of French soil which they had helped to win. Boats landed far from their targets. Units were scrambled and left without leaders and without direction.

And so the men dug in on that narrow strip of beach washed by waves and blood. They piled up by the thousands, shoulder to shoulder. Machineguns were set up a few feet from the water. Tanks that reached shore leveled their guns on the bluff to answer the enemy's accurate fire. Mortar crews manned their weapons/with the waves washing their boots. But nothing was moving off the beach. The invasion on Omaha Beach was a dead standstill! The battle was being fought at the water's edge!

I lay on the beach wanting to burrow into the gravel. And I thought: "This time we have failed! God, we have failed! Nothing has moved from this beach and soon, over that bluff, will come the Germans. They'll come swarming down on us …”

But as the minutes ticked by, no gray figures came off the bluffs. Our Navy was pouring a murderous fire into the enemy positions. From the beach too, disorganized as it was, there was a steady stream of small arms and machinegun fire. There was the heavy whack of the tank guns, too, and the thumping of mortars lobbing shells onto the bluff.

"We've got to get these men off the beach," Wyman said. "This is murder!"

Wyman studied the situation for a few minutes—and then with absolute disregard for his own life and safety, he stood up to expose himself to the enemy's fire. Calmly, he began moving lost units to their proper positions, organizing leadership for leaderless troops. He began to bring order out .of confusion and to give direction to this vast collection of inert manpower waiting only to be told what to do, where to go.

Paul Gale was a lanky, dependable right arm to the General and slight Lieutenant Robert J. Riekse of Battle Creek, Michigan, was his aide and messenger through a steady rain of shells and bullets. Riekse went down with a severe hip wound before the day ended, but until he did, he was a stout helper.

Up and down that bloody strip of beach we went from group to group, from soldier to soldier. Under Wyman's direction, messengers began moving between unit commanders. They stepped over the dead and wounded, flung themselves flat as shells whistled in to splatter them with mud and gravel, and then jumped up to carry out their orders. And gradually the fog of battle began to lift a little.

On another section of our beach, Colonel Taylor was engaged in the same heroic task of organizing the troops pinned to the beach by enemy fire. With equal disregard for his own life, he moved along the water's edge organizing the men of his beloved 16th. There was no place to go but forward, and Taylor knew the sooner his men began moving the fewer casualties there would be.

There were many heroes on Omaha Beach that bloody day, but none of greater stature than Wyman and Taylor. They formed the core of the steadying influence that slowly began to weld the 1st Division's broken spearhead into a fighting force under the muzzles of enemy guns. It's one thing to organize an attack while safely behind the lines—and quite another to do the same job under the direct fire of the enemy.

I tried to keep pace with the General and with Major Gale and Lieutenant Riekse as they moved along the beach, but at times it was impossible because of utter exhaustion. There were times when I had to lie on the gravel beside the dead and wounded until strength came back to my legs. It was difficult to see how those men kept going as they did without rest.

I remember a wounded boy moaning in delirium: "Oh, merciful God! Please stop the hurt! Get me out of here! Get me out of here!"

Poor kid! It would be hours before anyone could listen to his plea and get him into a boat. Beside us men dug shallow trenches in the gravel with their bare hands. Blood ran from their raw fingertips. Bodies of the dead floated in the water and moved gently with each incoming wave, relaxed and peaceful or stretched on the gravel in grotesque attitudes of frozen stillness. They had made their landing on another beachhead.

The wounded lay with eyes glazed by shock and pain and sometimes I helped them to crawl from the cold water which made them shake with chills. The medics worked over them staunching the flow of blood from wounds, easing pain with hypodermics, giving encouragement. The medics had no thought for themselves, or if they did gave no visible indication of it.

An LCVP ran onto a sand bar and the ramp lowered … a shell screamed into the craft and bodies hurtled into the water … men wading ashore with heavy equipment sank into the water without sound … jeeps ran down the ramps of boats and disappeared with their drivers … a youth came riding ashore on the rear of a half-track … suddenly he gave a startled gasp and slowly toppled into the water, a round black hole between his open eyes … Medic Peter Kuffner of New York City darted into the water and dragged him ashore, but his battle was ended.

Time had no meaning. Minutes dragged like hours. All sequence to events was lost. Those hours on Easy Red Beach were one long, endless nightmare recorded in memory in sharp unrelated scenes.

In one of them while the shells were flying thickest and bullets buzzed like hornets, Private Vincent Dove of Washington, D.C., calmly climbed into the seat of a bulldozer and began dozing a roadway off the beach—the first road over which tanks and trucks and guns could move. He sat up there on his 'dozer with only a sweat-soaked shirt to protect him from a slug of steel. He had driven a bulldozer for 15 years before he entered the army. He wasn't going to let the Germans stop him now! And by some miracle he lived through the fire pouring from the bluff, his bulldozer snorting defiance.

Vincent Dove must have given courage to hundreds of men who saw him atop his bulldozer doing the job he was sent to do.

I joined Gale on one of his missions. As we walked crouching near the water he suddenly yelled: "Down!" I flopped to the ground.

A shell exploded showering us with mud and gravel. Gale came running over. "Are you hurt?" he said.

I spat out a mouthful of mud. "No. I didn't even hear it coming. Thanks."

"I didn't either," he laughed. "I just felt it."

I felt better, then. If anyone could laugh at a time like this, everything would be all right. Death was a constant companion on Easy Red Beach. I found that if you walked hand in hand with death long enough, then there was no fear. Fear was replaced with a sort of fatalism. You were either going to get it or you weren't.

A runner, Lieutenant John P. Foley of Trenton, N. J., came to the General's command post to report our troops had broken through the enemy defenses and were moving off the beach! The youth was worn with fatigue and he had been nicked by a bullet over one eye as he made his way through enemy fire. He brought the news we had been waiting to hear. News that the tide of battle finally had turned in favor of the Fighting First.

"You've done a fine job, Lieutenant," Wyman said. "You've shown great initiative." He gave Foley an affectionate pat on the shoulder.

Wyman and Taylor organized groups to wipe out troublesome strongpoints and diverted units from their original missions to support hard-pressed units. The attack of the 16th began to have cohesion and drive.

Slim, sardonic Captain Joe Dawson from Texas led his company—what was left of it—out across the mined flats and up the bluff held by the Germans. The mighty tide that seemed so puny and futile in the early hours of invasion hammered its way forward.

One of the strongpoints holding up the First Division advance was a blockhouse at the edge of a roadway leading from the beach to the high ground beyond. It controlled the exit marked on the maps as E-1. An 88 poking its snout from an embrasure in the thick concrete poured deadly fire onto the beach.

A destroyer moved to within 500 yards of the beach in a daring maneuver and began firing at the blockhouse. One shell exploded squarely in the gun opening and knocked out the position. The roadway from the beach was open!

We didn't know it then, but the Fighting First had whipped an entire enemy division in the battle on the beach! The Red One had whipped a strong enemy entrenched in prepared positions, and it had driven him back!

Rommel's beach defenders never recovered from this blow. His main defense force was shattered. He had no reserves near with which to counterattack before the follow-up forces poured ashore to support the assault drive.

German batteries on our right flank continued to hammer the beach but the small arms and mortar fire began to fade at midday and Wyman and his little party made their way across the flats to the blockhouse knocked out by the destroyer's fire. And the blockhouse became Danger Forward—the First Division's first command post on the soil of France.

This blockhouse today is a memorial to those who gave their lives on Omaha Beach. It is beautifully landscaped and neatly trimmed grass and shrubbery cover the scars of D-Day. It will be a shrine for always for the mothers and fathers of those who gave their lives on Omaha Beach.

When we entered the blockhouse it still reeked with cordite fumes and the thick concrete walls echoed the explosions on the beach. But it was a sanctuary and to us it represented the solid inescapable fact that the First had a toehold on Hitler's Europe.

Danger Forward quickly became the nerve center of the battle. General Huebner and his staff came ashore to direct the operations at close range. They brought with them a sense of security and the knowledge that the First was once more a united force.

As the battle moved across the bluff, Huebner moved his command post with it. It was difficult to tell whether Danger Forward was in or behind the front line. All night rifles and burp-guns crackled around headquarters. Guns blazed as small groups of Germans attempted to fight their way from behind the American lines. Snipers were flushed from within a few yards of the command post and no one knew from what direction a bullet might come.

Through the tangled, matted Normandy hedgerows the men of the First fought their way forward. They captured Colleville, cut the main coast road, repulsed enemy counterattacks, and drove on to capture the strategic town of Caumont, sitting on a hill which dominated the left flank of the entire American beachhead.

Once the First had a toehold on the soil of France, there never was any doubt of the Red One reaching an objective. General Huebner's command post had an almost professional atmosphere of calm assurance. The First Division from top to bottom believed it was the best infantry division in the United States Army—and conducted itself accordingly. Even the headquarters company was willing and ready at all times to pitch into a scrap—and more than once the cooks and clerks and headquarters troops picked up their guns and helped turn the tide in the First Division campaigns.

But in all its battles in Africa, Sicily, France, Belgium and Germany, there never was one quite like the battle of Omaha Beach. In that battle alone the Fighting First won a niche among the immortals of American history. Huebner's men smashed the main strength of the Germans and by so doing turned the key that unlocked the door to victory in Europe. Behind them came the floodtide that overwhelmed the Nazis in the west.

General Eisenhower was keenly conscious of the tremendous role played by the First Division in helping him win the first round of the battle for Europe and of the magnificent fight of the 16th Regiment in spearheading the invasion on Omaha Beach.

One day early in July he visited Danger Forward accompanied by General Bradley. He pinned awards for heroism on the chests of 25 First Division heroes that day, and this is the story I wrote:

1st Division Command Post, France, July 2—(AP)—Heroes of the Fighting First Division who led the American assault on France and lived to cross that hellish strip of beach where so many courageous men died stood in the shade of tall Normandy elms today and received their accolade from General Eisenhower.

For the occasion they had tried to clean the stains of battle from their clothing, but still their uniforms showed they were just back from the front lines. No one cared about spit and polish with these men—least of all General Ike, who pinned Distinguished Service 'Crosses on the chests of 22 and gave Legion of Merit awards to two others.

These elite infantrymen had come through a test as great as any soldiers ever faced, and by their courage and leadership had opened the way for thousands of troops to follow.

They stood to attention on the lawn of an old gray chateau when jeeps carrying Generals Eisenhower, Bradley and Gerow halted before their ranks. General Ike jumped out of his jeep smiling. He wore a garrison cap, an air-force jacket belted at the waist, and his trousers were stuffed into paratroop boots.

He shook hands with Major General Clarence R. Huebner and then an officer began reading the names of the men receiving awards—

"Brigadier General Willard Wyman …"

On the thunderous morning of D-Day, this tall, square-jawed man moved up and down the beach with an absolute disregard for his own safety, getting troops organized and moving them inland to knock out enemy strongpoints.

Quietly he issued commands sending the doughboys against enemy strongpoints which were pouring murderous fire into our ranks, helpless on a shelf of gravel at the water's edge.

"Colonel George Taylor …"

This blue-eyed soldier had stood on the beach where thousands of his men were pinned down by enemy fire, and in a quiet drawl said, "Gentlemen, we're being killed here on the beach; let's move inland and be killed." And his men surged forward to break the German defenses and clear an exit from the beach which was a death-trap.

"Lieutenant Colonel Herbert Hicks of Spartanburg, S.C. …"

Troops under his command spearheaded the assault on Hitler's West Wall where a reinforced enemy division was waiting to meet them on the beaches behind concrete and steel fortifications. His gallantry and that of his men contributed greatly to the success of that bloody day.

"Major Charles E. Tetgmeyer, Hamilton, N. Y. …"

Under heavy fire, Tetgmeyer covered the length of the beach administering aid to the wounded. Time and again he went into the mine-strewn water and pulled wounded men behind the comparative safety of a shale barrier.

"Captain Joseph Dawson of Waco, Texas …"

Here was the man whose unit was the first to come off the beach and the citation said he was receiving the award for "extraordinary heroism." Deliberately he walked off the beach and moved across the minefields alone to draw enemy fire and give his men a chance to move in behind him.

"Captain Kimball Richmond of Windsor, Vermont …"

His assault boat grounded 400 yards from the beach, so Richmond and his men swam through a hail of artillery and machinegun fire. On the beach he organized his company and led it into the attack.

"Captain Thomas M. Marendino, Ventnor, N.J. …"

He led his men ashore and then, refusing to take cover from enemy fire, led a charge up a slope and overran a German strongpoint.

"Lieutenant Carl W. Giles, Gest, Kentucky. …”

His landing craft was sunk by enemy fire, but he swam ashore. He saw 3 men hit by enemy bullets fall into the water. He went back and pulled them to safety. Most officers of his unit were casualties and he assumed command and carried out the mission.

And on down the list to Pfc. Peter Cavaliere, Bristol, R.I., who stood before the four-star general with a carbine slung across his shoulder. Cavaliere went forward to set up an observation post and, surrounded by Germans, shot 8 himself and clung to the post helping to fight off enemy attacks in the critical hours of invasion.

Others on whom Eisenhower pinned DSC's were: Captain Victor R. Briggs of New York City; Lieutenant John N. Spaulding, Owensboro, Kentucky; 1st Sergeant Lawrence J. Fitzsimmons, New York; Staff Sergeant Curtis Colwell, Vicco, Kentucky; Staff Sergeant Philip C. Clark, Alliance, Ohio; Staff Sergeant David N. Radford, Danville, Virginia; Tech Sergeant Raymond F. Strojny, Taunton, Massachusetts; Staff Sergeant James A. Wells, St. Mary, West Virginia; Staff Sergeant Kenneth F. Peterson, Passaic, New Jersey; Tech Sergeant Phillip Streczyk, New York City; Sergeant Richard J. Gallagher, New York City; T/4 Stanley P. Appleby, Clarksville, New York; and Sergeant John Griffin, Troup, Texas.

The Legion of Merit was awarded Colonel William E. Waters of Louisville, Kentucky, and Master Sergeant Chester A. Demich of Burlington, Vermont.

As Eisenhower moved down the double rank, he spoke a few words to each man, asking him his job and where he came from in the States. And after pinning the medals on their worn combat jackets he called the men together in an informal group.

"I am not going to make a speech," he said. "But this simple little ceremony gives me an opportunity to come over here and, through you, say 'thanks.'

"You are one of the finest regiments in our Army. I shall always consider the 16th my Praetorian Guard. I would not have started the invasion without you …”

The First Division tipped the scales of invasion and lived up to the lyrics of their famed battle song: "The Fighting First will lead the way from hell to victory…”

© Copyright Mike Hanlon. All rights reserved.